A reproducible analysis

Context :

OK, the data is secured and cleaned.

You fire your fav IDE... Wait, you coded in notepad ?

Ok back to dev basics

Writing great code

What to expect from your code

One of the key skill of any developer, including data scientist, is to communicate business logic through code. Since the beginning of software development in the 50s, collaboration has been a difficult question to tackle. It has only been solved through specific tools and shared practices in order to make code readable and modifiable by anyone. Good code is extremely difficult to describe. Here are some ideas:

- It is elegant: it uses well the programming language features to solve the tasks at hand

- It is readable: if you need 10 lines of comment to explain each line of code, then you might need to rethink your function and variables names

- It is simple: no unnecessary refinements

When it comes to data science, code quality allows project management, but even more importantly, makes the project reproducible. This particular problem still plagues some if not most of the statistics research, and parts of machine learning research. Way too often we see code that are basically a collection of script without proper order. These models are usually inaccurate and die quickly if the data scientist quit his job.

Trying to write great code, applying craftsmanship is a core is thus a core concern for scientific validity as well as doing great data product.

Choose an IDE that helps you

Integrated Development Environment are text editors dedicated to code development. It ranges from extra lightweight fired from shell to cumbersome full of helpful feature. Here is some of the best python editors at the moment:

- Vim and Nano... yes it works. But it requires a high proficiency

- Sublim Text and Atom had their moments of glory, but were never fully optimized for python

- PyCharm is a complete IDE. But it's quite a heavy one.

- VSCode is the new kid in the block. It's python features are almost finished, and with the right extensions you can get really productive

Now most of these IDE have extensions that can help you:

- code conventions (pep8 / flake8)

- auto formatting

- refactoring

- integrated python repl

Choose an IDE that helps you, and invest seriously some time to try some of these extensions that would correct your mistakes. This avoids a lot of errors in production...

Writing Scripts

A proper scripting needs parameters

Most code written by data scientist is basically script, with little place left to advanced programming features. However, they don't usually take any arguments and are simply lines and lines of code without organization. Fortunately, Python provides an out-of-the-box argument parser, argparse. Let's suppose we want to train a model, and that we have one parameter, alpha. A quite common script would be:

from my_package.models import DummyModel, save_model

import argparse

# let's suppose we have a function to train a model

def train_model(X_path, y_path, alpha=0.1):

model = DummyModel(alpha=0.1)

X = pd.read_parquet(X_path)

y = pd.read_parquet(y_path)

model.fit(X, y)

print("Alpha value is %s" % model.alpha)

save_model(model, "model.pkl")

if __name__ == "__main__":

parser = argparse.ArgumentParser(

description="Train a model."

)

# we need to give the name of X file, and the y file as well.

# with alpha, it makes three parameters.

parser.add_argument("--alpha", help="ML parameter", default=0.1)

parser.add_argument("--X", help="input", default="feature.parquet")

parser.add_argument("--y", help="target", default="target.parquet")

args = parser.parse_args()

# here we call the

train_model(args.X, args.y, alpha=args.alpha)

At run time, this simple script would be used in the following way:

$ python script.py --help

usage: script.py [-h] [--alpha ALPHA]

Train a model.

optional arguments:

-h, --help show this help message and exit

--alpha ALPHA ML parameter

$ python script.py --X data/processed/features.parquet -y data/raw/target.parquet

Alpha value is 0.1

$ python script.py --alpha 0.7

Alpha value is 0.7

With this small reorganisation, it is easy to trigger different models training, add some tests and so on. However, this script is still isolated from other tasks the data scientist has in mind.

Better scripting with DAG pipelines

Data science projects chains multiple steps, such as data collection, feature engineering, model training and so on. Scikit-learn introduced pipelines, which is chaining different data processing steps in the same execution. Pipelines are not always linear,they are here called DAGs, for Directed Acyclic Graph. That's where Prefect comes in. This python package allows running several tasks with decent logging, execution and scheduling. Here is a DAG example:

from prefect import Flow, task, Parameter

import argparse

import boto3

import pandas as pd

from sklearn.linear_model import LogisticRegression

from skl2onnx import convert_sklearn

from skl2onnx.common.data_types import FloatTensorType

s3 = boto3.client('s3')

# First, we download versionned data

@task

def get_data(version):

distant_file = "mydataset/%s/X.parquet" % version

s3.download_file('datasets', distant_file, 'data/X.parquet')

return pd.read_parquet('data/X.parquet')

@task

def get_target(version):

distant_file = "mydataset/%s/y.parquet" % version

s3.download_file('datasets', distant_file, 'data/y.parquet')

return pd.read_parquet('data/y.parquet')

# The usual ML stuff

@task

def make_features(X):

X = X

# do some magic here

return X

@task

def train(X, y):

model = LogisticRegression()

# add smoe cross validation and test/train as needed

# or some mlflow ?

model.fit(X, y)

return model

# Upload the model to s3

@task

def persist(model, version):

# Convert into ONNX format with onnxmltools

initial_type = [('float_input', FloatTensorType([1, 4]))]

onx = convert_sklearn(model, initial_types=initial_type)

with open("target/rf_iris.onnx", "wb") as f:

f.write(onx.SerializeToString())

object_name = 'mydataset/v0.1/model.onnx'

s3.upload_file('target/rf_iris.onnx', "dataset", object_name)

# Define a DAG as a flow

with Flow("My Awesome Flow") as flow:

version = Parameter("version")

X = get_data(version)

y = get_target(version)

X_features = make_features(X)

model = train(X, y)

persist(model, version)

# run with "python script.py --version v0.1"

if __name__ == "__main__":

parser = argparse.ArgumentParser(description='Process some integers.')

parser.add_argument('--version')

args = parser.parse_args()

# we run the flow

flow.run(version=args.version)

This DAG is fairly simple, but effective. A good way to improve it would be to introduce distant storage, like S3, for models and datasets. If you are fortunate enough to have on-point data engineers and ML engineers, they will likely talk about Apache Airflow. This technology goes a step further, and allow long running workflow on pretty much any infrastructure. Go check it. A contender for DAG scripting is Luigi.

Reproducible environment

Python environment

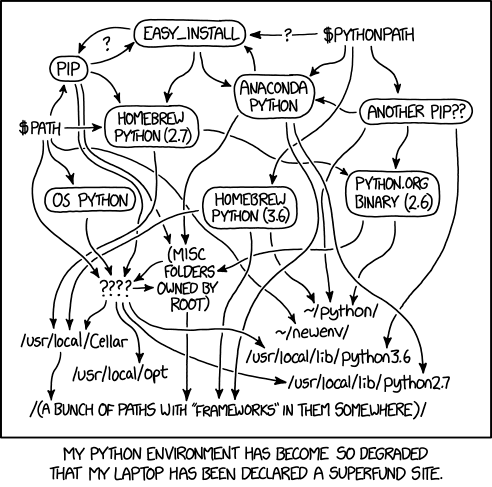

Python environment are a way to manage multiple python setup in the same computer. Sometimes, ML projects uses libraries that are not compatible together. Env are most definitely a good practice. However, they are quite tricky to get right, as outlined by Xkcd:

The pip/virtualenv choice is the default on classic python distribution. If you are a data scientist, you should have heard of pip and pypi already. Now let's see how to create a virtual python environment for a new project:

$ pip install virtualenv

# boot a virtualenv

$ virtualenv my_virtualenv

# the virtual environment is stored in the my_virtualenv folder

# let's enter this environment

$ source my_virtualenv/bin/activate

# let's check which python

(my_virtualenv) $ which pip

/path/to/project/venv/bin/pip

Obviously the venv folder is full of binaries and should go straight to gitignore. So you can't send it to production as is. There is a way to make a portable specification of the environment, which is the requirements.txt file. It is a list of packages installed that can be simply reinstalled with pip. There are several ways to generate this file. The command pip freeze allows to list the different packages within the active environment, which can then be written to the file. However, the freeze command list all the packages, some of which can be inferred from dependencies. A tool of choice is the pipreqs package. It walks through the project code only, match found import ... with the environment package. It results in a lighter, cleaner requirements file.

$ pip freeze > requirements.txt

# alternate, simpler option

$ pipreqs --use-local .

# to install packages in a new environment

$ pip install -r requirements.txt

Conda is a different beast altogether. Many python packages uses C/C++ code underneath, which are tricky to install. Conda manages both packages and binaries in the same go, and thus doesn't require compilers. All theses reasons means it a sturdier option to pip.

Conda also has an environment management. Instead of creating a local folder, it brings all environments in the same location, which makes easier to share environments between projects.

$ conda create --name my_virtualenv

$ conda activate my_virtualenv

# use pip inside the env

(my_virtualenv) $ conda install pip

(my_virtualenv) $ pip install whatever # or conda install whatever

# conda list --export shouldn't be used here.

(my_virtualenv) $ conda env export > environment.yml

$ conda env create --name second_env --file environment.yml

# pipreqs or pip freeze is still a valid option

(my_virtualenv) $ pipreqs --use-local .

(new_env) $ pip install -r requirements.txt

Now what a data scientist would need would be to update frequently the requirements or environment file since it's the first step to replicate the environment used for the experiment.

Containers for environment setup

Python packages aren't the only setup some projects needs to run. For example, an ML api might run on a server such as nginx. That's where container comes in. Containers are small virtual computer that you can run basically anywhere. It offers a clean machine to run code. There are three main use cases:

- Once the data scientist has developed the code, it is necessary to test that the code works in a brand new environment. This is part of integration testing.

- It also offers a convenient way to retrain model without knowing much about how the code is done.

- And it is quite handy when doing prediction on a new dataset.

The equivalent of environments are called images. They are build with a requirement file called a Dockerfile. When this image is run, the active environment is called a container. Let's see an example:

# start with a basic 3.6 python image

FROM python:3.6

# let's copy our code to project folder and cd to there

COPY my_project /project

WORKDIR /project

# building the environment

RUN pip install -r requirements.txt

RUN pip install awscli

# let's store the dataset name in an enviroment variable

ENV VERSION v0.1

# grab the data from the

# run a script that grab the data from a S3 and do stuff on it

CMD python script.py --version $VERSION

Now to build and run it, the commands are as follow:

# lets built it

$ docker build --tag my_project_image --file Dockerfile .

# we can see it exists now

$ docker images

# let's run it, changing the $DATASET environment var with a new dataset name

$ docker run -e VERSION=v0.2 my_project_image

A convenient use of container is that once this image is built, it can be run multiple times with different parameters. Let's say you want to run twice the container with different datasets to compare training results. We use the environment variable to trigger different computations easily.

This is only a rough outline on how docker work. Ask your data engineers on good practice on that.

Todo list

- My worflow is defined by pipelines and/or scripts

- It pulls data from distant storage (like S3) automatically to fill the data/raw folder

- My requirements.txt is updated regularly

- I test that my code in a container to see if it's reproducible.

Note : one thing that wasn't presented here is code testing.

Reading list

| type | TL;DR | date | link |

|---|---|---|---|

| reprod | some ideas about reproducibility | 2017 | link |

| reprod | R reproducibility | link | |

| ML | Great rules from Google | link | |

| ML | A mandatory reading on technical debt | 2014 | link |

| ML | Another mandatory reading on production systems | 2016 | link |

| Pipeline | Sample of Amazon | 2016 | link |